| |

As a child, I knew René Barde at the end of his life. We lived in the same building on rue Ernest Renan in post-war Paris...

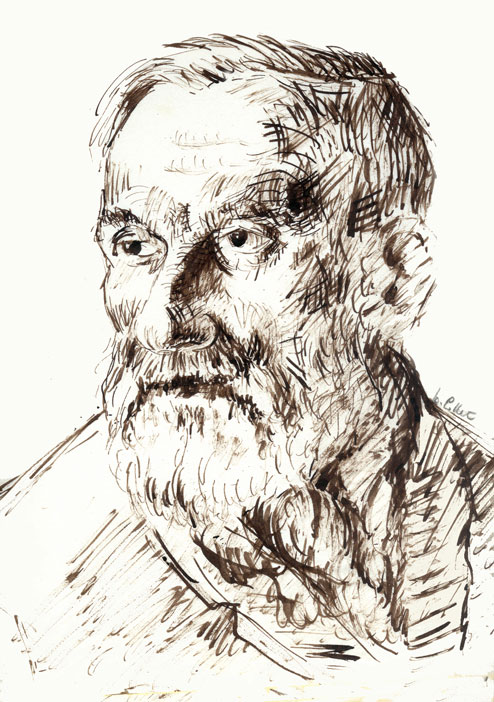

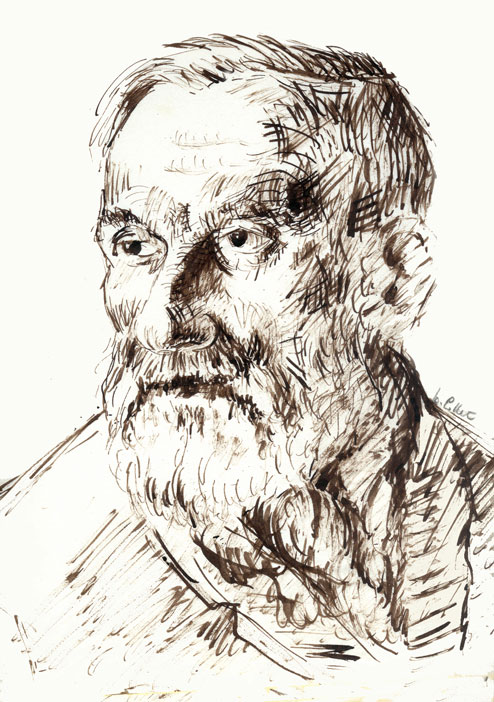

With his slightly arched silhouette, his patriarchal face with hollow cheeks gnawed on by a grey beard, his old dark and mismatched clothes, he was a familiar and reassuring figure to me. We were crossing each other on the stairs when I was running down my three floors and he was struggling back up to his attic with his black oilcloth bag at the end of his arm. Seeking to catch his breath, he had to stop often, holding on with one hand to the ramp. His chest swelling and deflating like a gusset, he could only respond to my salvation with a smile that I guessed under his grey beard.

I then took his bag from him and rushes him up to the sixth to drop him off at his door, while he continued his slow ascent. Sometimes he would ask me to wait and let me choose a piece of candy sugar from a small round metal box.

In my late teens, I became familiar with his attic under the roof. I was curious about this tiny little room with no heating and grey plaster walls. Between the cage-bed that ate half of it, and an old wooden table from which stacks of books, notebooks and papers rose on blackened wooden shelves up to the ceiling, there was only the place for a chair and a narrow passage to the window. Attic storey, it opened onto the gutter, the sparrows and the roofs of Paris. For any "decoration" clothes and linen hung on the ceiling from strings such as rabbit skins that have been turned over and dried in a barn. Punched on the wall facing the window, a large watercolour depicting trees, at the bottom was written: "To René, my long-time friend, Gable 55". On a shelf in the "office" between his manuscripts and the Bhagavad-Gitâ, meditated on a crouching buddha of golden plaster. Below was a picture of Ramakrishna.

From the few general reflections of good cordiality to the teenager, René will confide more to the young idealist I was becoming. Starting from my rough moral assertions, my artistic beginnings, or my political a-priori, he will reveal to me hidden ideological foundations, will let me glimpse as many perspectives the distant developments of reflection, or, at the turn of a remark, guess the virtual harvest of ideas from an analysis.

He invited artists or poets, Brazilian saints or bandits, statesmen or prophets to his talks. Marx, Jesus, Van Gogh, Beethoven or Bach, Khrisna Murti or Freud lived for a moment in his soupente. Evoking the bare feet pounding the earth to the rhythm of the heart in front of the Indian temples, the resistance of the humble to exploitation, the blood offered to the sun at the top of the Mayan pyramids, or the enigmatic Marabout of the Moroccan steppe, he widened the world for me.

Yet I felt his suffering, trapped in this body prematurely aged by poverty and asceticism. Her solitude too, where her overly full temperament had enclosed her. At times his gaze became distant, on his face passed like a pale and unfathomable sadness. What failed dreams, what unfinished trials came from this silent distress? Sometimes, on the contrary, it was in Dantean roar that he called hell on the executioners of Algiers, or the hypocritical and cowardly leaders, that he denounced the bleached tombs of the double-sided prelates, or called the atomic bombs on the corrupt peoples. The harshness of his thinking then placed me a few landmarks to support my life.

He never gave me the opportunity to read any of his writings. It was only after his death that I discovered them, a huge manuscript that had been revised many times, three proverb notebooks, countless notes thrown day after day from a tight writing on all kinds of pieces of paper, and then this autobiography that I knew he was working on. He said that it would be necessary for those who would come to read his book, to situate its genesis and development. In fact, it is a work in itself where the unusual trajectory of a human adventure unfolds: from his harsh childhood when, in the violence of his environment, he develops respect for life and silently expands within him spaces of contemplation and spirituality, from the young peasant, who at random friendships, and encounters gets somewhat educated, from the second-hand worker, companion of the marginalized and downgraded, who begins to write in Paris between the two world wars. He also frequented the whimsical world of painters that his childhood friend Édouard Pignon introduced him to. A fertile and shady friendship will bind him to the Italian painter Orazi.

The roughness of his self-taught writings and his fierce convictions earned him the attention of Romain Rolland, Marcel Martinet, Gabriel Marcel and Léon Chestov.

He will pursue a long and obstinate quest for the absolute at the cost of destitution, physical suffering, spiritual anguish until his death.

This book tells the story of this slow counting, which others will call "descent into hell".

When I met him, at the end of this odyssey, his internalized gaze was still on the world and the life of fierce gleams, but could also mist up with tears in front of a blade of grass or a child's gaze. His exhausted body, where life still resisted a little, became as if transparent. Wasn't he an angel in his attic under the roofs? Alone, overwhelmed by the life he had imposed on himself, it was with a breath of victory that his story ended: "It is without fear that I see the present approaching the other side. Yes, really, I won the game. »

René Barde had long since stopped trying to publish:". My work? Fate, providence will decide, the tree will not sell its fruits" he said, and it is to me, as to a basket of wicker on the river that he will entrust his writings by will... It has been more than 45 years since he died in my arms one winter day in 1963. The basket did not sink, and fate placed Said Mohamed on his wandering. May he be thanked for "bringing out" this dark and ardent life, that of my friend René.

Bernard M. Collet, Spring 2008

|

|